Among the various themes treated by Chillventa 2020, also the issue on which intervened Bente Tranholm-Schwarz, DG CLIMA European Commission, outlining the state-of-the-art on the F-Gas Regulation, the revision in course and matters and aspects this review will have to take into account.

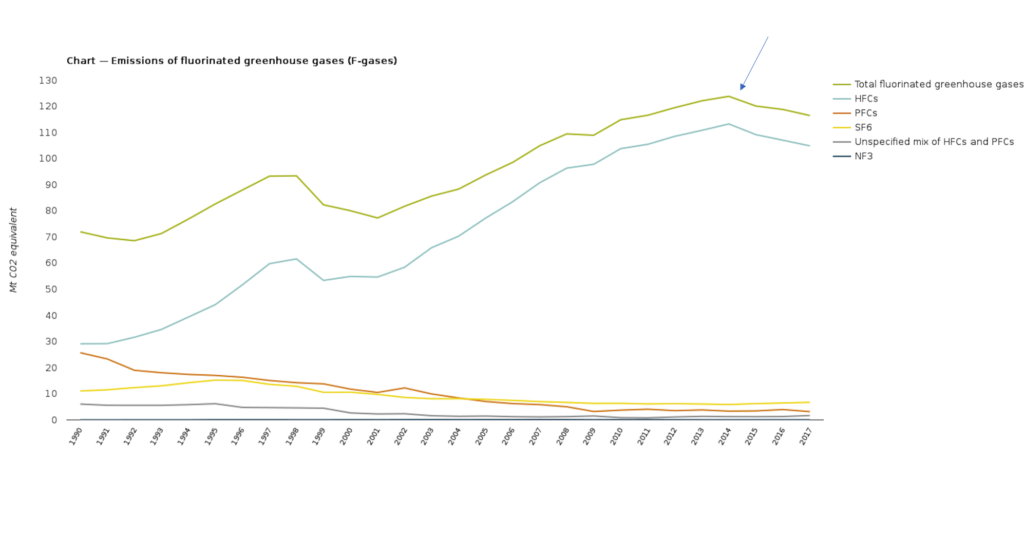

What is the state-of-the-art, first of all? According to what reported by EEA – European Environmental Agency – the emissions of fluorinated gases more than doubled in Europe from 1990 to 2014. With the coming into force of the F-Gas Regulation, this trend stopped and currently F-Gases feature a decreasing tendency, according to what provided for by the gradual reduction imposed by the F-Gas Regulation.

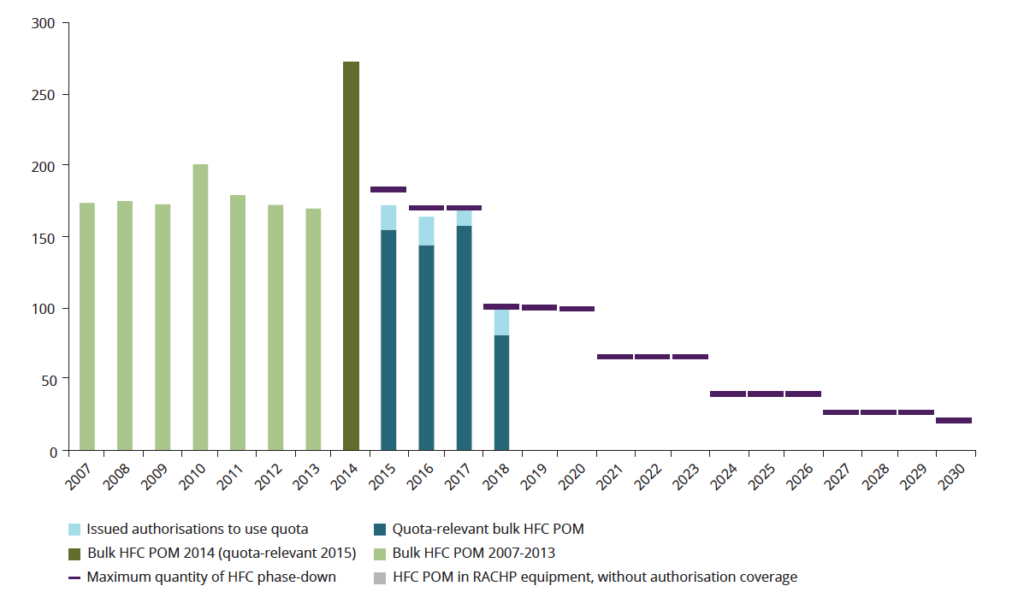

The phase-down – the global reduction of refrigerants with high GWP on the European market – is running according to plans, at least in official numbers. Not only the quantity of refrigerants in equivalent tons is diminishing but also the typology of refrigerants is changing. Pre-charged systems that reach the EU market, for instance, contain less and less R-407C (GWP 1774) and R-410A (GWP: 2088), and more and more R-32, which with its GWP of 675 represents a medium-term solution to transport users towards 2030. A recent report by the Commission that examines the sustainable alternatives for split conditioners for residential use confirms this trend and indicates R-290 (propane) as possible alternative for splits <7kW and R-32 as alternative for higher-power splits.

The regulation, anyway, must be revised for three main reasons:

- Since when it has come into force, Europe has set more ambitious climatic targets. With the Green Deal Strategy, the target of reducing emissions by 40% within 2030 must be risen to at least 55% to reach the climatic neutrality in 2030. The sector that uses fluorinated gas must suit these new goals, too, today significantly different from 2015;

- In 2016, Kigali Amendment to Montreal Protocol came into force and its targets widely go beyond 2030, where on the contrary the F-Gas Regulation stops. To remain in conformity with Montreal Protocol, Europe must establish some post-2030 strategies;

- There are some aspects of the Regulation that must be improved to have the opportunity of monitoring better refrigerant traffics.

In the light of these three facts, the Commission asks the following questions:

- Is it necessary to define more severe reductions within 2030?

- Are further bans in the use of HFC necessary?

- Are post-2030 reduction phases necessary?

- Is it necessary to eliminate some of the currently existing exemptions from the Regulation?

- Might the creation of a one-stop customs shop improve the controls on refrigerant trade?

- What measures should be implemented to prevent the abuse of shares?

Lessons learned from the Regulation until now

The overall Regulation balance until today outlined by Tranholm-Schwarz is in general positive. In particular, she affirms: «In recent years, technology has lived an impressive development towards sustainable technologies and industry itself states that, concerning this, many sustainable technologies are available». However, in many cases technology is not missing but instead those who must install it miss its knowledge.

Revision process: what is the progress?

The revision process of the F-Gas Regulation has already started. Concerning this, the Commission has also launched a public consultation to which all EU citizens have been invited to participate. The consultation ended in December. According to the results of this consultation and of meetings with the sector, the Commission will evaluate the impacts and the results reached until now by the Regulation and eventual new provisions.

Afterwards, by the end of 2021, the Commission will propose its modifications to the European Parliament and Council and the latter will decide if and how to adopt them. Such discussion is supposed to last until 2022-2023, when the new Regulation is finally expected to be born.

In the meantime?

Meanwhile Tranholm-Schwarz never stops repeating what each conscious stakeholder knows and, in his turn, should unceasingly reaffirm, and what we have stated several times in these pages, too: let us not wait for the date of coming into force of bans to shift to alternative solutions but let us do that as soon as possible. Today we decide what we will do tomorrow and what problems we will have to face: if falling into the trap of being compelled to use hardly available refrigerants at stratospheric prices or to achieve a relatively tranquil future for the plant lifecycle.

“Refrigerants AND energy efficiency” and not “refrigerants OR energy efficiency”!

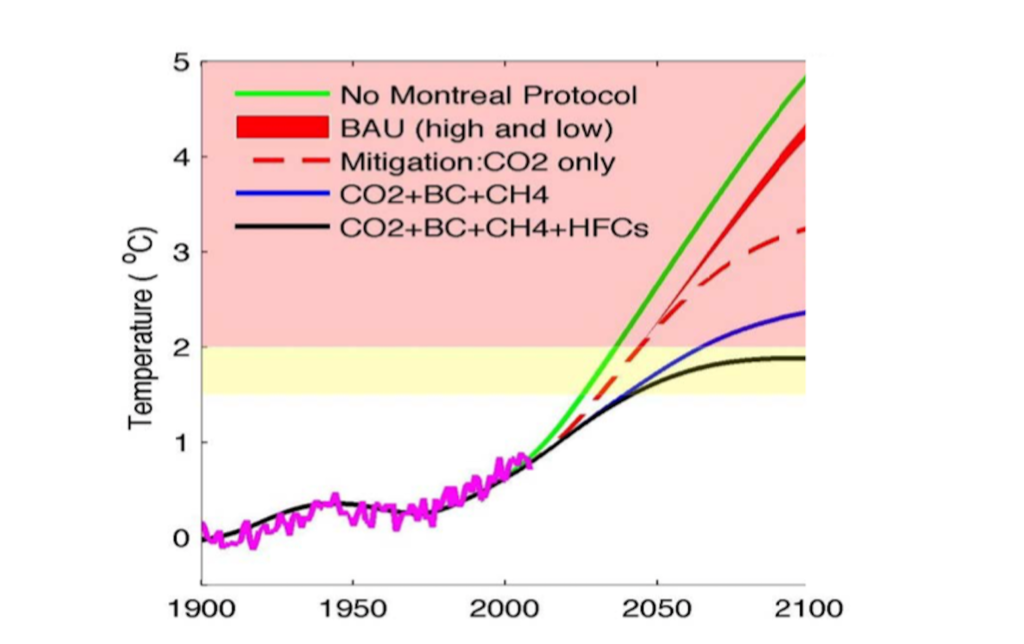

During the session of questions addressed to the Commission, someone pointed out that currently plants’ direct emissions are only a minor part of total emissions and the energy consumption does instead the lion’s share. For this reason, it would be indispensable to focus on the energy efficiency and not on refrigerants. Such argument, although it may seem to have its own logic, is very short-sighted. First of all, plants’ direct emissions will increase considerably in the next future, considering the rise of the number of appliances for which the cold sector is intended. But, especially, there are scientific studies that clearly highlight how just the simultaneous control of both emissions – direct and indirect – allows remaining well under a rise of global average temperature of 2°C. Finally, Tranholm-Schwarz affirms: «New sustainable technologies stand out also for their better energy efficiency, indicating how refrigerants with low GWP and energy efficiency are not an oxymoron» and that it is possible – not only a must – to work simultaneously on both fronts.

From the report on the emissions of fluorinated gases by EEA

- The refrigeration sector is still the major absolute user of fluorinated gases, in 2019 employing as much as 63% of fluorinated gases on the EU market. Therefore, it is clear that when it is decided to diminish these emissions, among all sectors that use fluorinated gases, most attention must be paid to the refrigeration ambit;

- The introduction on the market of fluorinated gases, both in their totality and just considering HFC, is decreasing both in tons and in equivalent CO2 and this has happened since 2015.

- The emissions of F-gases have been decreasing since 2015, too. Although this is taking place quite slowly, scenario models calculated in 2012 to estimate the difference of effects between the 2006 regulation and the 2014 regulation indicate that the differences in terms of emissions would have been considerable if the F-gas Regulation had not been introduced. The emissions of such gases would have been actually out of control;

- The decrease of HFC (in equivalent CO2) measured for the RAC sector indicates a rise of the use of alternative and natural gases

New ideas for the review of the F-gas Regulation

In September, the European ONG ECOS (https://ecostandard.org) invited the European Commission to take a bolder stance in the review in progress of the regulation about fluorinated gases and to accelerate the gradual reduction of highly polluting fluorinated gases. Together with other environmental associations, ECOS has submitted a series of modification proposals of the regulation about fluorinated gases. Some of the proposals are the following:

- Promoting an acceleration of the programme of gradual HFC elimination, modifying the penultimate stage in 2027 at 10% of reduction instead of 24%, as it is currently foreseen, and the final phase in 2030 at 5% instead of 21%.

- Adopting a sound system of HFC licenses in real time based on the system of ODS licenses, which needs licenses for the shipment of all HFC, including exempted HFC and HFC in transit.

- Eliminating the exemption from shares for the producers and the importers that introduce on the market less than 100 tons of CO2eq

- Assigning a cost to HFC shares and distributing them through an auction or an assignment commission, using revenues to support the implementation and the enforcement by member States and to facilitate the adoption of climate-friendly technologies.

- Including minimal civil sanctions in the revised regulation on fluorinated gases, based on a multiplier of the HFC seizure value, which must be cashed by the Commission and requiring penal sanctions for specific violations in member States.·

- Adopting a vigilance and coordination policy of the market at EU level for the regulation on fluorinated gases·

- Requiring that the certification programmes established by member States include compulsory competences on natural refrigerants and alternative technologies, including practical training structures that allow a practical training on pertinent systems.·

- Asking for an update of obsolete standards to allow the introduction of safe energy-efficient climate-friendly technologies, in particular those based on A3 refrigerants. European regulations should support the minimal technical requisites for all potential charge sizes and should be explicitly established in the revised regulation on fluorinated gases.·

- Requiring member States to promote incentive systems and to revise policies about GPP to promote the introduction of alternative technologies.·

- Including immediate bans for the sub-sectors that should have been already converted into HFC-free alternatives based on available natural refrigeration technologies.

- Aligning the regulation on fluorinated gases with the Paris Agreement and evaluating the impact on the climate of a gradual accelerated reduction of HFC of EU and of the market bans in terms of GWP20 in parallel with the current GWP100, to provide political managers and public with an accurate snapshot of the real short-term effect of the refrigerants released into the atmosphere.